Garren is a real estate research analyst who works for an Edmonton-based real estate advocacy organization. Previously, he worked for one of Canada’s most well-known property data and advisory firms. Garren graduated from FFCA High School (now FFCA North High School) in 2014 and earned a B.A. in Urban Studies and a Master of Management (MMgmt) from the University of Calgary in 2019 and 2021, respectively. He was a student in Ms. Hunnisett’s Grade 10 and 11 English Language Arts classes in 2012 and 2013.

Dazzling, delighting and enthusing spectators with their luminous lights, shimmering glass, and intricate mullions, exteriors are the first visible features of buildings. With full exposure to the elements, the outside appearance often prepares onlookers for the inside experience. Beautiful building façades piqued my interest during my youth, culminating in an overwhelming fascination with architecture. However, exterior showcases often conceal interior nuances, an all-too-common issue in the real estate space. The contrast between external appearance and internal qualities, ironically, mirrors my journey in the sector.

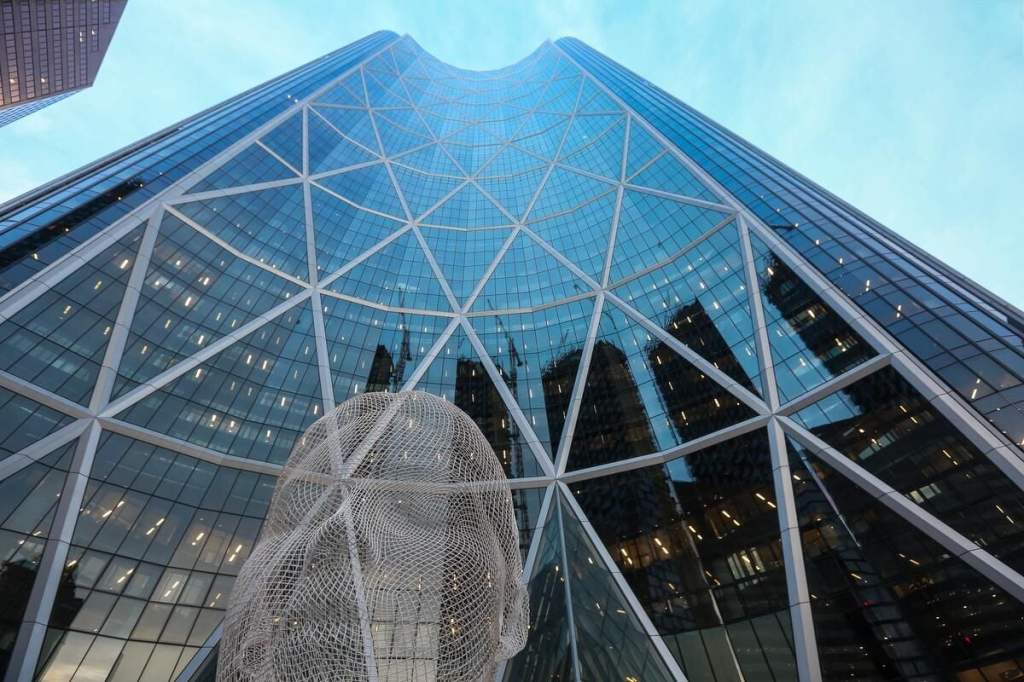

In the summer of 2008, at age eleven, I emigrated to Canada and settled in Calgary. At that time, the city was at the tail-end of the 2000’s oil and gas boom, which spurred many high-rise projects. I was particularly fascinated by The Bow, a 236-metre office skyscraper that was unlike any of its Calgary counterparts. Its overhead crescent shape vastly differed from the prototypical boxiness of adjacent skyscrapers. Its diagrid lattice façade contrasted with the squarish mullions of neighbouring high-rises. Its glass cladding diverged from the steel, concrete, and brick-laden exteriors of nearby buildings.

As a teenager, I enjoyed observing The Bow ascend the Calgary skyline. At that time, the building was one-of-a-kind in the city; from my perspective as a young chap, The Bow was one of many flashy high-rise proposals from that economic epoch. Architects unveiled a frenzy of eye-popping proposals that, amidst a depressed global economy in the late 2000’s coupled with record low interest rates, led to record-breaking buildings. The Burj Khalifa topped out at 828 metres and remains the only building globally to eclipse the 800-metre mark. The 80,000-seat Beijing National Stadium, nicknamed “The Bird’s Nest”, boasts the title as the world’s largest steel stadium. The Shard, a 301-metre skyscraper named for its resemblance to a shard of glass, graced the London skyline.

The concurrence of immaculate building proposals during this time influenced my decision to pursue architecture. I believed, naïvely, that becoming an architect was key to being able to design buildings that were just as beautiful.

Despite this belief, when it came time for post-secondary applications, I did not pursue a Bachelor of Architecture degree. Neither did such a program exist at the undergraduate level in Alberta, nor was I willing to borrow student loans to pursue out-of-province education. Instead, I remained in Calgary and enrolled in the recommended program: Urban Studies. While I was uncertain what that entailed, I learned lots about city-building forces that I previously disregarded, notably the significance of the interstitial space between buildings. Other learnings included considerations for form, function, and the surrounding building context. I realized that my fascination with architecture was strictly with the aesthetics. Buildings, I discovered, transcend their exterior and physical space.

During my last undergraduate semester, I used my final elective on a Master of Architecture (MArch) course. This class presented the opportunity to incorporate my knowledge and skills, which I hoped would preview my later educational aspirations. Instead, that class exposed the downsides of architecture, both for students and professionals. Architecture students are said to dedicate more out-of-class time to complete coursework – by necessity – than students of any other major. My classmates were overly focused on perfecting their designs; these creations were subsequently lambasted by instructors and professionals alike. Many of the students were extremely stressed and sleep-deprived.

My observations and discoveries in the class incited my disillusionment with the architecture field. Witnessing my classmates’ agony daily, the façade of an externally prestigious profession was declad, revealing a hollow interior and a mirror of my academic and professional future. My peers’ struggles, had I pursued a MArch, would soon be my bleak reality.

These realizations greatly contributed to my inability to secure employment in the subsequent three years. I struggled to find a viable substitute for architecture. The combination of an unclear career path and the knock-on effects of a two-year pandemic complexified my job hunt, something that even attaining a master’s degree could not ameliorate.

In early 2022, I started a role as a research coordinator (later rising to a senior market analyst) at one of Canada’s largest real estate advisory firms, analyzing commercial real estate transactions in Calgary and Edmonton. My expectations for the role were initially low because I failed to grasp its significance beyond the stated position requirements. However, I thrived in the role and developed an aptitude for analyzing the key statistics of commercial real estate assets. Statistics are fundamental to informing buy, sell, hold, or development decisions in the real estate space. While architecture reveals what property owners desire to project, it is the statistics that reveal the underlying truths about the asset.

As I worked in this role, I discovered my love of statistical real estate research. It is the figures that enable analysts to unearth the subsurface realities. The hidden truths of buildings became more apparent, often depressingly so. For example, roughly 30% of the Burj Khalifa’s building space is uninhabited because the demand for dwellings hundreds of metres in the sky is rather low. The Bird’s Nest is extremely capital-intensive because it lacks permanent tenants and struggles to attract tourists, creating a sterile environment. The Shard lacks accessibility and contains high vacancies due to absentee condominium unit owners and empty office suites.

Over the last three years, my growing disillusionment with architecture has paralleled my increasing interest in real estate statistics. Architecture is rife with pretentiousness, with trivialities often posing as the main features. In contrast, real estate statistics expose the internal truths, pleasant or disturbing. This newfound passion is a far cry from my starry-eyed fascination with buildings from my youth, but it elicits similar levels of joy and excitement all these years later.

LinkedIn account: https://www.linkedin.com/in/garrensharpe/

Leave a comment